Jeopardizing Patient Access to Medicines in Medicare

Right now, Medicare Part D plans use competition to obtain significant discounts on brand medicines and offer a wide range of coverage and treatment options. Seniors enrolled in Part D have, on average, 24 to 32 plan options to choose from in each state, helping them find the plan that best fits their needs. As a result, nearly nine in ten seniors consistently report they are satisfied with their Part D coverage. But the price setting policies in the Inflation Reduction Act change how Part D works and are predicted to lead to fewer choices and less robust access to medicines for seniors. While Part D plans are required to cover medicines that are selected for price setting, there are no policies protecting access to other medicines. To adapt to the changing Part D structure and to extract as much money out of the program as possible, Part D plans will likely rely on more utilization management and move more medicines to more expensive non-preferred and specialty tiers in their formularies. The result is more barriers to medicines for seniors enrolled in Part D.

Additionally, the price setting policies in the Inflation Reduction Act change how doctors who administer selected Part B medicines are paid, making it even more difficult for them to provide needed medicines to their patients. Doctors will now be reimbursed by Medicare based on the much lower government-set price for selected medicines instead of the market-based price used today, which could also inadvertently impact reimbursement in the commercial market as well. These changes mean it may now be more difficult for doctors to afford to administer these Part B medicines, disproportionately affecting community providers and those in rural areas, potentially reducing access to treatments and forcing seniors to travel farther to get the care they need.

Undermining R&D Critical for Patients

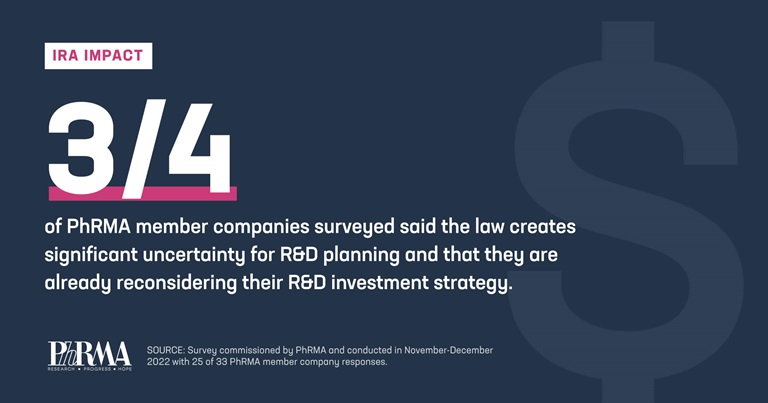

The price setting provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act are already impacting R&D decisions, resulting in companies rethinking their approach to R&D. Some companies are cutting projects and reallocating resources, while others are reconsidering whether to offer medicines in the United States because they may never be able to recoup R&D costs.

According to a survey of PhRMA member companies, 78% of respondents said they expect to cancel early-stage pipeline projects that no longer make sense given the short timelines before medicines could be subject to government price setting. Two-thirds of companies said certain pipeline projects not yet in clinical development will likely no longer be pursued. The provisions are pitting disease areas against each other, forcing companies to make difficult choices and, ultimately, patients are the ones who will lose out with fewer new treatment options in development.

Discouraging R&D of Small Molecule Medicines

However, the price setting provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act discourage the development of small molecule medicines by starting the process for price setting on these medications earlier in their lifespan. Medicines that come in pill or tablet form can be chosen for price setting seven years after they’ve first been approved by the FDA with the set price taking effect two years later, only nine years after the medicine was initially approved. This is far earlier than the time before small molecule medicines currently face generic competition, 13 to 14 years on average. This discourages companies from investing in their development to begin with. Companies should be able to make decisions based on patient needs and science, not on misguided government reimbursement policies, which is the likely outcome of the law’s policies.

Jeopardizing Post-Approval R&D

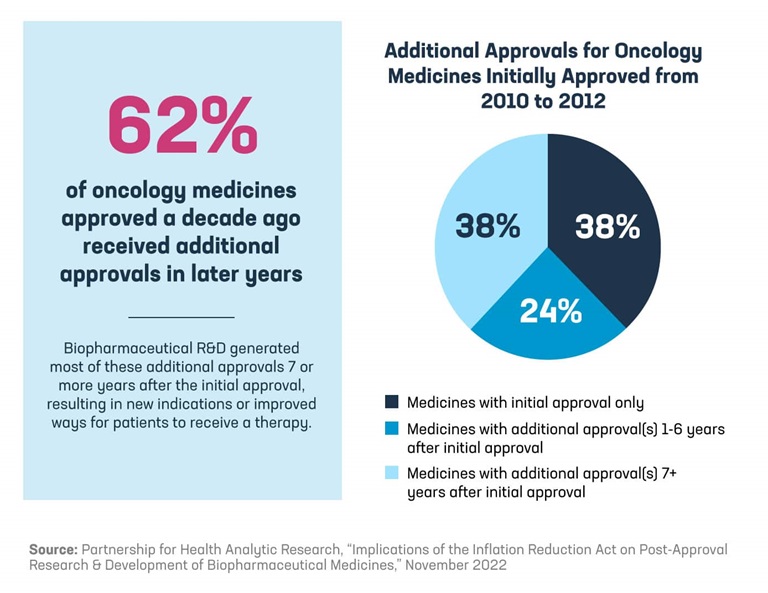

More than 60% of oncology medicines approved a decade ago received additional approvals in later years, and a majority of those medicines received a new indication seven or more years after approval. In cancer, these later indications may provide important treatment options for patients newly diagnosed with cancer or demonstrate the ability to extend a patient’s overall survival.

Because the price setting provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act can begin at pre-defined times after a medicine is initially approved, they ignore the R&D process that continues in the years following a medicine’s approval and discourage researchers from following promising scientific leads. Facing the significant uncertainty under the law’s price setting process, companies may make the difficult decision to stop conducting the necessary clinical trials up to four years before possible selection for price setting. Biopharmaceutical companies have no incentive to invest in post-approval research if the government can set the price of a medicine long before companies even complete the additional research and obtain approval for the additional indications.

Policymakers should make it a priority to preserve innovation in lifesaving treatments and medicines for hard-to-treat conditions, like rare diseases and cancer, and protect access to these innovations. They should also focus on finding more ways to lower what patients pay out of pocket for medicines by addressing abusive practices of insurers and PBMs. PhRMA will continue fighting for policies that lower what patients pay out of pocket and protect future biopharmaceutical R&D.